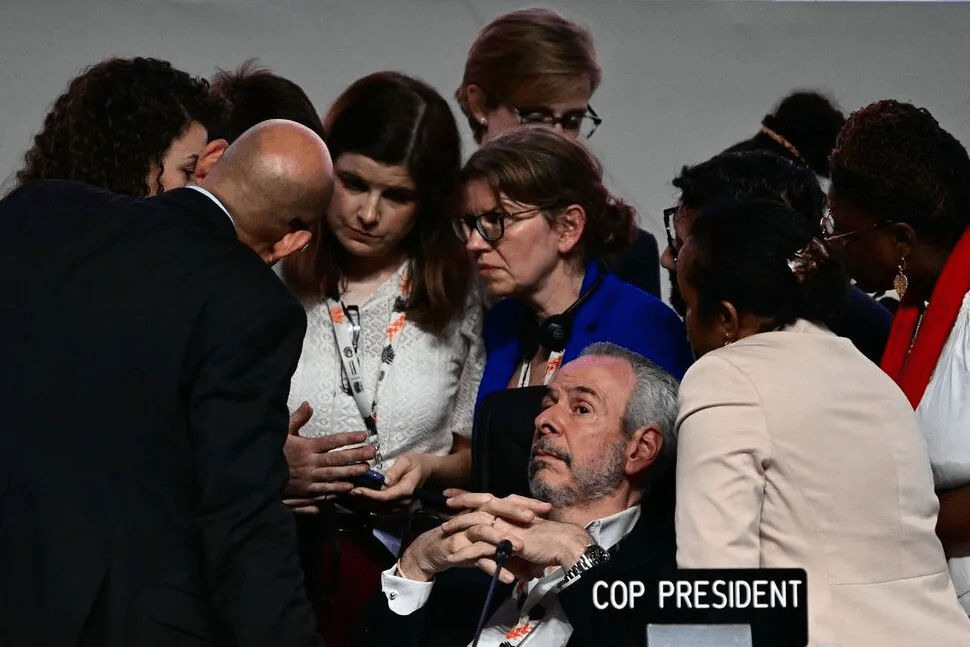

As Brazil’s “Climate Summit” (the 30th UN Climate Change Conference of the Parties, COP30) came to a close, many observers say the final decision text fell short of expectations, notably with the disappearance of explicit language on “fossil fuels.” Although there were some achievements—such as tripling finance for developing countries’ climate adaptation efforts and establishing mechanisms for a “just transition” to protect the rights of workers, women, and Indigenous peoples—the overall outcome was insufficient to provide a turning point in the world’s long-stalled climate response.

Above all, many point to the absence of global leadership as one of the key reasons.

■ Disappearance of Pressure from the U.S. and China

China, the world’s current largest greenhouse-gas emitter and a country expected by some to step into a leadership role in place of the U.S., fell short of those expectations. Despite leading global renewable-energy industries—including solar panels and wind turbines—it remained largely silent throughout negotiations on emission reductions, support for low-income countries, and preventing deforestation. This reflected its consistent stance of emphasizing “developed countries’ responsibility” from the perspective of developing nations. China also played a major role in inserting language into the final text stating that “climate action must not be used as a pretext to restrict trade,” clearly aimed at the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM).

Columnist Jonathan Watts wrote that if “the world’s largest historical emitter and the world’s current largest emitter had been able to coordinate a joint approach, as they did before the Trump presidency, many of the disputes surrounding the negotiations could have been avoided.” With the U.S. absent and China silent, “it is no surprise that Saudi Arabia felt emboldened to block any references to fossil fuels at the summit.”

The New York Times noted that although the U.S. has not always been a champion of ambitious climate action, it has historically served as a source of pressure on large emitters such as China and Saudi Arabia. This time, that “source of pressure disappeared.”

■ Individual National Interests Prevail Over Cooperation

Brazil, as the host country, had raised expectations by emphasizing “climate justice” and the protection of the Amazon rainforest in the lead-up to the conference. But it faced criticism for approving domestic offshore oil drilling projects just before the summit opened. President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva made a last-minute push to advance implementation plans for a “transition away from fossil fuels,” but the host-country-led “Mutirão (community cooperation) decision text” ultimately fell short.

The European Union—historically a self-declared leader in climate ambition and the world’s second-largest emitter in historical terms—also made little impact. With the rise of far-right forces internally, the EU has struggled to maintain its leadership. As a result, it delayed finalizing its new Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC), which aims for a 66.25–72.5% cut in emissions compared to 1990 levels by 2035, and only submitted its updated NDC to the UNFCCC Secretariat on December 5.

While the EU joined more than 80 countries in calling for the development of an implementation plan for “transitioning away from fossil fuels,” it was criticized for its cautious stance in negotiations on “adaptation finance” to support developing countries. Some suspected this was a strategy to shift focus away from adaptation funding by spotlighting fossil-fuel-related measures.

“America walked away, and China stepped back,” Jonathan Watts observed in The Guardian. The United States—historically the largest emitter and currently the second-largest—did not attend the climate summit for the first time in 30 years. President Donald Trump’s administration has taken a distinctly anti-climate stance, including rolling back support for electric vehicles and solar energy and reviving the fossil-fuel industry. Trump’s return to power weakened the “Amazon Climate Summit” long before it even began.

In contrast, Colombia emerged as a vocal leader in calling for the end of fossil fuels. It issued the “Belém Declaration” alongside more than 80 countries, calling for a phase-out of fossil fuels, and plans to host a related meeting in April next year. Colombia clarified that this meeting is meant to supplement, not replace, existing UN processes.

■ Calls for Systemic Reform Likely to Grow

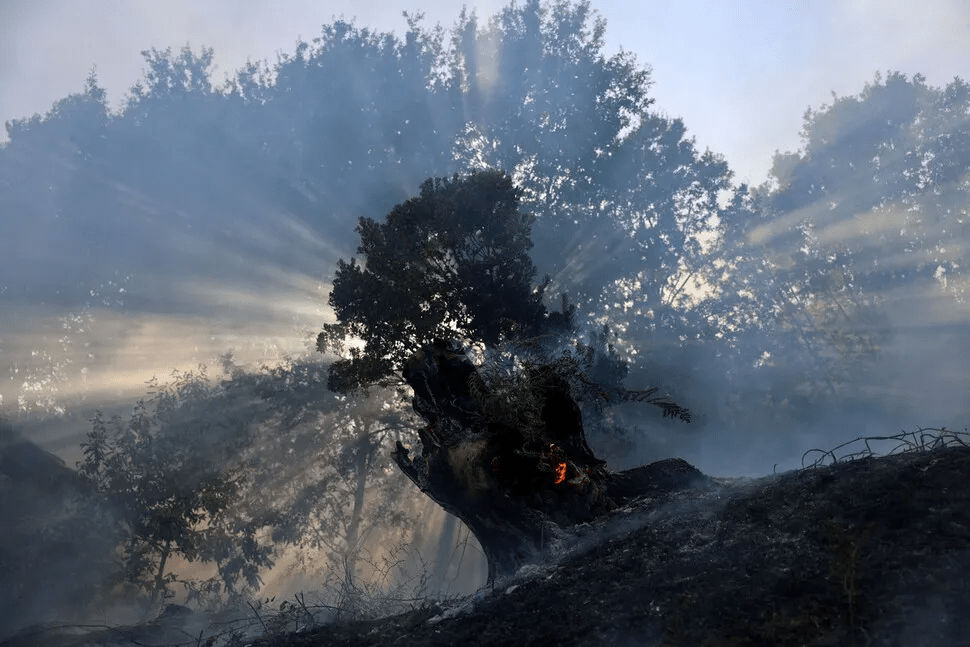

The international community’s failure to agree on any implementation plan for phasing out fossil fuels—the primary driver of anthropogenic greenhouse-gas emissions—has intensified criticism of the current architecture of global climate governance.

The Center for International Environmental Law (CIEL) argued immediately after the summit that the agreement is “a violation of law,” given the absence of commitments to a “complete and equitable phase-out of fossil fuels” and the lack of adequate, public climate finance. The organization argued that the final text ignores the International Court of Justice’s legal opinion that all countries are obligated to keep global warming below 1.5°C.

Chief counsel Erika Lennon stressed that the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) itself must be reformed—starting with implementing conflict-of-interest rules and allowing majority voting. The UNFCCC currently requires “consensus” for decision-making, effectively operating under a unanimity rule, which critics argue allows major emitters and oil-producing states to block meaningful progress.

Jonathan Watts put it this way: “A single country can exercise a veto, yet the physical reality of climate change offers no veto. We need a more innovative and dynamic system of governance.”

댓글 남기기